As I write this, it's early July, 2013, another a year of more drought and fires in Colorado and the Southwestern US. Friends and former neighbors of mine in the Black Forest, near Colorado Springs, are recovering from damaged or destroyed homes during a recent human-caused fire. The Wolf Creek Fire Complex near Durango, ignited by lightning, still burns largely out-of-control, and sadly, 19 firefighters lost their lives in a monstrous blaze last week in Arizona. The Royal Gorge attraction in Canon City, CO, has been shut down due to a forest fire there several weeks ago. Fires burn in Nevada. It seems like the whole western US is up in flames.

I'm saddened at the loss of life, homes, and businesses in these and the other areas affected by fires this year. It's been a rough season already with a few more months of fire danger still to come.

|

| Smoke from the Wolf Creek Fire darkening the canyons south of Mesa Verde. |

But those of us in drought-prone areas also realize that naturally-caused fire is, and has been, a way of life here for centuries, if not millenia. As our human population grows and more people move west and want to live in the mountains and forests, we would do well to come to terms with and accept our surroundings. Perhaps even finding ways to adapt to them.

There's no doubt that we're in the middle of a regional drought here in the Southwest USA. Some areas are harder-hit than others which makes them more prone to wildfires. And the situation doesn't show any signs of going away any time soon. Drought here is cyclic and it's something we can't stop, much as we'd like. The Ancient inhabitants of this area knew this all too well. Cyclic water and resource depletion, due in part to drought, have negatively impacted the Ancient Pueblo People, the Aztecs, Hohokam, Mayans, and many other groups for at least 2,000 years (and probably more).

Draining the rivers to irrigate our fields, green our lawns, or fill our reservoirs doesn't solve the problem. Only Mother Nature can do that by delivering more rain and snow and cooler temperatures. When the rain and snow don't come, the risk of wildfire increases.

During this time of fires I took a trip to Mesa Verde, near Cortez and Durango, CO, a much more drought-prone area of the Colorado than where I live, near Boulder. Mesa Verde reminded me yet again that naturally-caused fire is a "normal" part of the cycle of forests here in the west.*

Mesa Verde has had a volatile record of droughts over the last 1000 or so years. Persistent drought may be one of the reasons that the Ancient Puebloans left these canyons over 800 years ago and moved south. Over that millenium, fire has been a recurring visitor to Mesa Verde.

Just looking at Mesa Verde teaches us that the forests will survive, the animals will return, and what we see happening now is really just a point in time in the natural cycle of life here in the Southwest US.

Mature pinyon and juniper forests gave Mesa Verde its Spanish name, "Green Table."

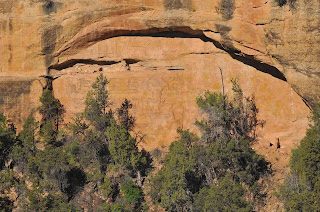

An unburned area of Mesa Verde National Park.

Mature pinyon and juniper trees near cliff dwellings.

Rainfall here is sparse but is enough to support a forest of pinyon, juniper, rabbitbrush, scrub oak, creosote bush, sage, and mountain mahogany. Native flowers include many species of penstemon, native sunflower, arrowleaf balsamroot, native buckwheats, and wild roses.

But sometimes lightning from a dry thunderstorm sets off a blaze that consumes the forest and resets the cycle. Dead trees and shrubs, duff, and leaf litter are cleared. Fires have consumed much of Mesa Verde's mature forests in the last 15 years. The large trees I saw in this National Park when I was a child have been mostly burned off since the late 1990s.

Some burn areas are interrupted by stands of unburned trees, often due to the efforts of firefighters to contain the blaze:

Old growth pinyon and juniper (foreground) with a recent burn scar from 2005 in the middle ground, Mesa

A recovering burn area. Large, burned trees are being replaced with shrubs such as oak and rabbitbrush.

After an area burns it's more prone to mudslides and flash floods. But this risk gives way as dormant seeds in the soil sprout and take root (see pic, above). These new plants send out roots that lock the soil in place and the frequency of floods and mudslides subsides.

And as with the Phoenix, with a forest fire comes eventual rebirth. Besides killing off live trees, the blaze clears off dead trees and shrubs, duff, and leaf litter that were blocking light and water from reaching the soil. Now that the soil has light and water, plants grow and flower from roots or dormant seeds, such as this penstemon blooming near Step House, Mesa Verde:

Some trees and shrubs, such as the Ponderosa Pine, Sequoia, and ceanothus, are naturally resistant to mild/moderate ground fires. Others, mainly conifers like the lodgepole and Bishop pines, need fire to force cones open to release their seeds. Without fire, these trees' seeds would never germinate.

From the human perspective, recent burns at Mesa Verde have done something pretty interesting for archaeologists and visitors to the park. Burned areas can give us an idea of what the region looked like when the Ancestral Puebloans lived here. At that time, around 1000-1300 AD, the mesa tops were cleared and planted with corn, beans, and squash. The landscape would have looked similar to the picture below, taken near the Long House ruin. The inhabitants of the area removed the trees in the canyons for firewood and building timbers, leaving the valleys relatively bare and clear:

A recent burn near Long House, showing what the area might have looked like 1100 AD.

But we know by just taking a look around Mesa Verde that, given a chance, the trees and shrubs do come back and the forest renews itself. We learn that naturally-caused wildfires are part of the cycle of life here in the dry West. For Nature, fire isn't the end of the world, it's the start of the next cycle.

How do we humans deal with and perhaps even adapt to living with fire? More to come in my next post...

*Notice I write "naturally-caused" fire. I don't consider blazes like the one in the Black Forest, caused by humans, to be "natural," so this blog post does not apply to them. Human-caused fire is not really part of the natural cycle of a forest even if drought conditions were present at the start of the blaze.

For more information, see:

http://techalive.mtu.edu/meec/module11/FireandJackPine.htm

http://www.fire.ca.gov/communications/downloads/fact_sheets/live_w_fire.pdf

http://www.werc.usgs.gov/OLDsitedata/seki/pdfs/regeneration.pdf

http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/